When Richard Drew of 3M developed creped paper masking tape in 1925, he began a revolutionary change in the way we live. From that first step, taking us from the over-a-century-old, cloth-backed, pressure-sensitive tape for surgical use to the many and varied industrial tapes that followed, Drew’s tape changed how we make and do things. It is used in the manufacturing process, in the finished product, or on the packaging of just about everything in our daily lives.

Adhesive tape has served in the most noble of our endeavors. A roll of coated cloth adhesive tape known as "mission tape" goes on board every American mission into space. It was that tape that helped jury-rig the carbon dioxide filter that saved the lives of three astronauts on the ill-fated Apollo 13 mission.

The Need for Training of Forensic Scientists

Unfortunately, the criminal element has also discovered the thousands of uses for adhesive tape, and it is being found more and more often as trace evidence at crime scenes. By far the most common tape found as evidence in two out of three cases involving adhesive tape is duct tape. It has been used in the packaging of illegal drugs, as a gag and ligature, and in the disposal of murder victims. The next most common tape-as-evidence is vinyl electrical tape, usually found in explosive devices but used for other purposes, too, including ligatures. In the last five and a half years, around 600 cases have been identified where vinyl electrical tape had been used in constructing explosive devices. Lesser-used tapes include masking tape, polypropylene packaging tape and filament tape.

PSTC now lists thousands of different commercial adhesive tapes in its product directory. To those made and sold by manufacturers in this country, we can add the imports and private-branded products sold by distributors or those found in the consumer market. This includes a variety of tapes from various countries in the Far East, not to mention Germany, Italy, Poland and other parts of the world. There are over 100 different duct tapes listed in the PSTC Directory; if we consider differences in color, that number goes up to over 250. When adhesive tape is found as evidence, the forensic scientist (whose proper title is "criminalist") must find his or her way through this maze with little or no knowledge of tape construction. They must first identify the tape and then confirm beyond a shadow of a doubt that it is the same type of tape as that found elsewhere, which usually means in the possession of the suspect.

The Crime Laboratory

The typical crime laboratory is a far cry from those shown in the various CSI television programs where one technician does everything. The modern criminalist usually decides to specialize in one aspect of evidence examination. The criminalistics section of a typical large forensics laboratory is divided into a number of lesser labs, each with its own specialist(s). These mini-labs cover the following areas of investigation:

- DNA

- Latent prints

- Questioned documents

- Hairs and fibers

- Illicit drugs, poisons

- Firearms, explosives, tool marks

- Arson

- Trace evidence (coatings, plastics, glass, adhesive tapes)

Trace evidence can wind up being a catchall, and in a smaller lab, hairs, fibers, and even tool marks may also wind up in that group. Needless to say, that’s where adhesive tape also winds up, regardless of evidence size. While the criminalist is studying for his or her specific degree in criminalistics, it is rare for any training on adhesive tape examination and analysis to be given. In receiving adhesive tape as evidence for examination, the first thing an inexperienced criminalist would be expected to do would be to turn to published literature for help. Unfortunately, none of the standard forensics textbooks offer anything specific on adhesive tape examination and testing. Further, whatever has been published in forensics journals over the years is slight, scattered and spans quite a few years and countries. Published technical papers are typically concerned with the testing of a specific type of tape, and almost all of them are related to vinyl electrical tapes. So, it becomes very difficult to find a broad-spectrum article on adhesive tape that could be used as ‘basic’ training.

With adhesive tape appearing more and more as trace evidence, the FBI Academy added adhesive tape examination and analysis to their one-week coatings course some years ago. The FBI was able to provide the necessary training on the various analytical methods that could be used for adhesive tape examination but looked to the adhesive tape industry for an instructor who could provide firsthand knowledge of adhesive tape design, manufacture and unique features. After a couple of false starts, they finally recruited Jerry Serra, Ph.D., of Tyco Adhesives, who in turn recruited the author. This has proved to be very successful endeavor, and, with the ever-increasing need for training in adhesive tape examination and analysis, the FBI Academy now offers a one-week course devoted solely to adhesive tape examination and analysis. Over the last three or four years, criminalists from across the country who have attended the FBI course have arranged for similar presentations on adhesive tape examination and analysis to be given at their own area conferences and workshops.

What the Adhesive Tape Industry Can Offer

It is worth noting that, apart from the jurisprudence aspect, the adhesive tape chemist has much in common with the trace evidence criminalist. They both must be experts in a range of materials (covering plastics, films, coatings, polymers, fibers, textiles, glass filaments and fillers) and must know something about the processes that produce each. Each must also be skilled in product analysis and knowledgeable in the best analytical procedures to generate the maximum number of answers.

When dealing with adhesive tapes as evidence, everything comes down to an investigator’s ability to accurately match the evidence tape with a similar tape in a suspect’s possession. Therefore, the number of points of agreement (and even disagreement) can be very significant in confirming or eliminating the possible source of the tape. The forensic scientist would normally follow such routine methods of analysis as the physical examination of the various tape components and the infrared spectra of each.

What an instructor from the adhesive tape industry brings to the table, however, is a detailed knowledge of the common types of pressure-sensitive adhesives used in various tapes, as well as their possible components, chemistries and solubility. Added to this are the many ways in which an adhesive tape can be constructed. A detailed knowledge of the myriad backings used in tape construction—and their chemistries—can be provided, not to mention the multiple coatings involved. This includes cover release and prime coats, backsize coatings, and saturants, which indicate the possible components and chemistry of each coating. Finally, the adhesive tape industry expert possesses the requisite knowledge to discern the subtle ways in which alternate designs and processes can differentiate one tape from another.

Adhesive Tape Subtleties

There are many subtleties within a given type of tape that are not readily apparent to the untrained eye but can add considerably to the ways in which the evidence tape and a tape roll are alike or different. Most of these tests are easy to do and can quickly exclude various candidates prior to starting more complex testing procedures. Such subtleties may include:

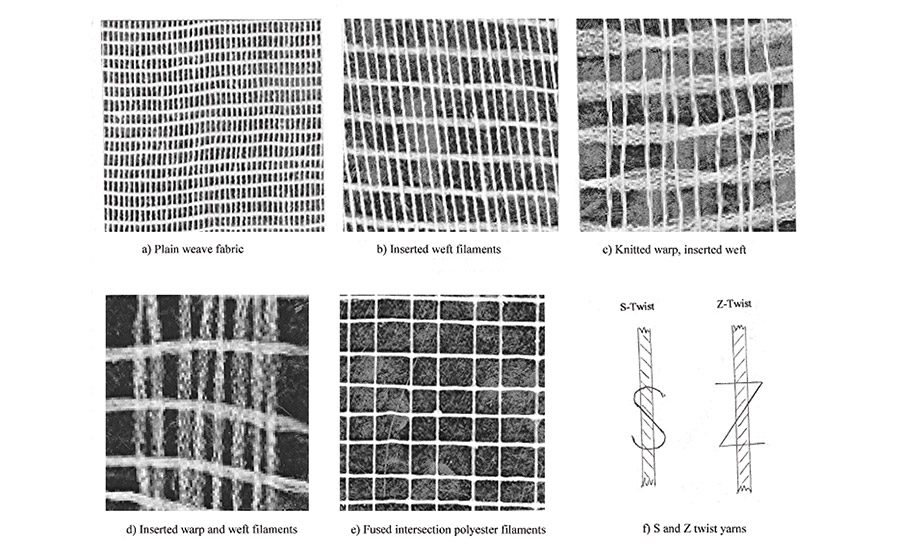

- The various types of fabric weaves that are used in the construction of a duct tape. Added to this is cloth count, yarn chemistry, yarn weight and twist, all of which help to isolate a specific duct tape.

- The chemical nature of the yarn in the fabric, which can be quickly identified under polarized light.

- The small impressions in the polyethylene backing found in an extruded film duct tape and their significance.

- The creping of masking tape paper, and which side has been coated with adhesive.

- The significance and variety of bubbles in the adhesive of a tape, and how they differ based on their origin.

- The physical edge differences that result from different slitting techniques.

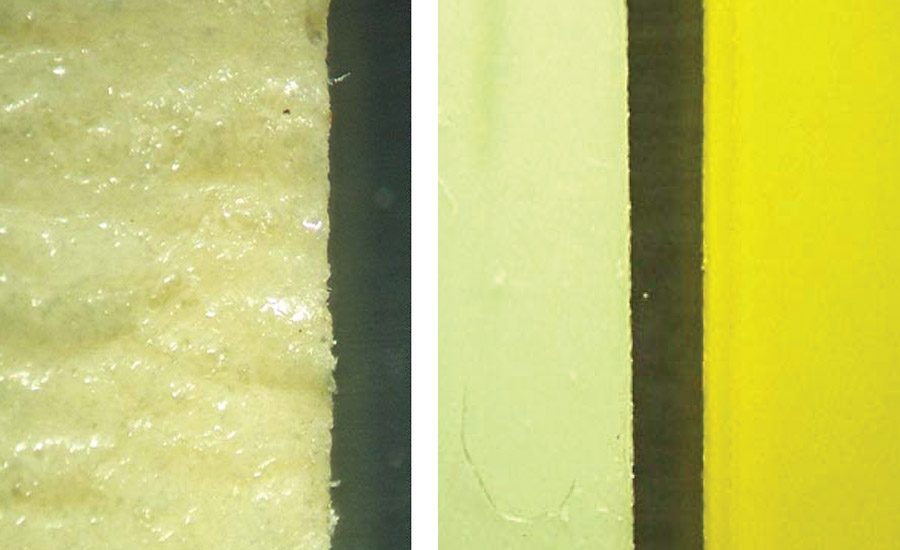

- The use of tape cross-sections in identifying multi-layer film backings.

- The differing optical characteristics of transparent-oriented film under polarized light, based on film thickness.

- The effect of ultraviolet light on certain tapes.

- The components of the film backings of PVC electrical tapes, and the means to identify them by energy dispersive x-ray analysis.

- The awareness that a latent print is left by a pressure-sensitive tape after removal, which can help identify the type of tape used.

It is also important to point out that an adhesive tape can be a collector of other trace evidence (e.g., hairs and fibers) that warrants careful examination. While it is extremely rare for the adhesive of adhesive tape to be touched by hand during the manufacturing process, it is impossible not to touch the adhesive surface when using the tape manually, which means there could be a useable latent print somewhere on the tape surface.

Training

Almost all of the above characteristics are easy to demonstrate, and there’s no easier way to learn than hands-on experience. “Adhesive Tape as Trace Evidence” classes held across the country presently provide each attendee with a basic test equipment kit and a range of test samples. The test kit consists of a cloth counting glass, a simple X30 pocket microscope, an ultraviolet light, a pick, a soft black pencil, two small sheets of Polaroid® film, creped paper and a selection of various tape samples. As each feature is discussed, the attendees can then investigate that feature for themselves using the samples and equipment provided. Three or four “unknown” tapes are then given out, and each attendee is asked to generate as much information as possible on each unknown using techniques already demonstrated. The results are then compared and contrasted in general discussion.

Instructors stress that even when all of the many characteristics of the evidence tape agree with those same characteristics found in a roll of tape belonging to a suspect, all that can be said is that a high probability exists that the two are related. The only true way to know that an evidence tape originated from a suspect’s tape is by matching the torn edges.

Until forensic training in adhesive tape technology, examination and analysis becomes part of a regular university training curriculum, it is hoped that the adhesive tape industry as a whole (perhaps by acting through the Pressure Sensitive Tape Council) could expand its educational objectives and take ownership of this worthy cause. Adhesive tape companies—particularly duct tape manufacturers—can also assist in the education of scientific law enforcement by offering guided tours of their manufacturing facilities. When an adhesive tape company is asked to assist in criminal cases involving adhesive tape, it would be helpful to have a specific individual within that company assigned to act as coordinator. With cooperation from the corporate level all the way to the individual, we can all help to put the bad guys where they belong.

Acknowledgements

My thanks go to Jerry Serra, Ph.D., Covalence Adhesives Inc., and to Jenny Smith of the Jefferson City Crime Lab, Jefferson, Mo., for their input. I also wish to thank those adhesive tape companies and suppliers that have kindly provided samples for use in the present education program.

This paper was presented at the Pressure Sensitive Tape Council Tech 30 Global Conference VI in May 2007 in Orlando. For more information on PSTC and the next technical seminar, visit www.pstc.org.