Compliance Systems: Then and Now

Compliance

is now a strategic objective, not just a collection of tactical projects.

Overlapping compliance requirements cry out for an encompassing architectural

approach.

A recent Aberdeen report on Compliance and Traceability provides insight into the development and maturation of manufacturers’ compliance programs. Best-in-class manufacturers understand that compliance programs are not just necessary activities, but a competitive advantage. The report relates that best-in-class companies are working toward common, single and enterprise compliance systems, and replacing outdated manual and one-off, non-integrated tools.

The report highlighted pitfalls that hamper most compliance initiatives: focusing on document rather than process management and a lack of metrics to measure success.

Why is it that focusing on process is such a challenge? To understand, we need to understand the history of compliance programs. In the 1980s and ‘90s, compliance programs were “checklist” audits. The effort to achieve compliance focused on having an answer for every item on the auditors' “checklists.” Companies focused on spreadsheets and manuals to meet early compliance requests. With the recent round of corporate corruption, front-page recalls and other high profile, compliance-related debacles, compliance has turned into a bottom line assurance that the process is operating in a safe and effective manner. Therefore, corporate and industry compliance programs are now focused on effective process. It is no longer acceptable to simply “have the answers” - inspectors want to know how you got the answers.

One additional challenge in the old way of doing things was the myriad governmental, industry and client standards that had to be met (e.g., ISO9000, AS9100, 21CFR11, TS16949, GMPs, ISO13485, etc.). It was not unusual for an organization to have 3-4 ongoing compliance initiatives, each with their own manual and checklists to pass each individual test. The good news about a process orientation is that once compliance is “built-in” to a process, the effort to demonstrate compliance requires minimal added labor, and audits go much smoother. A recent study by AMR Research concluded: “As business and IT recognize the overlapping requirements of individual compliance mandates, leaders are taking steps to build out a sustainable architecture that minimizes time and cost while maximizing future reuse.” (Source: AMR Research)

Strategic Actions to Addressing

Compliance Pressures

Strategic Actions to Addressing

Compliance Pressures

A common framework for compliance initiatives is the backbone of process approach to built-in compliance. It allows for common information to be distributed and kept up to date. It provides distributed teams with the ability to work together off of one source of information. In complex manufacturing, this not only helps with compliance but provides companies that employ this strategy with a competitive advantage to reduce cycle time and reduce costs.

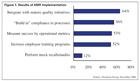

When AMR looked at how to develop this active compliance framework, they asked survey participants who had achieved best-in-class status how they had implemented the framework. The results are shown in Figure 1.

Not surprisingly, most organizations leveraged mature quality initiatives. There are two types of “quality.” First, there is quality control, which is a measurement function at the back end of the process. While an important part of manufacturing, this is not the type of quality that the survey is referring to. Quality management is the life cycle-long approach of building in quality functions to the manufacturing process that the survey refers to as “mature quality initiatives.”

Much like ERP streamlined the inventory and financial aspects of manufacturing, Enterprise Quality Management (EQM) is now providing that same streamlining function to the rest of manufacturing operations.

“The new role of the quality professional is to provide the organization with a seamless, integrated view of the business,” said John M. Cachat, chairman, IQS Inc. “The Quality Organization must provide the answers that cannot be found in financial and ERP systems.”

Organizations have tried vaulting documents and sharing them, but the result is that operations, inspection, purchasing and quality functions need data and information - not necessarily documents.

Process-orientation has two components: deriving information

critical to the process and sharing the information across the process

efficiently.

Process-orientation has two components: deriving information

critical to the process and sharing the information across the process

efficiently.

When investigations begin on a quality failure, rarely is the answer that no one in the organization knew the problem existed, but that not all of the people in the organization that needed the information had it.

So start at the beginning. Gather the pieces. Share them. It

sounds simple, but in reality, with the amount and complexity of information

required in manufacturing today, gathering and sharing requires sophisticated

technology.

So start at the beginning. Gather the pieces. Share them. It

sounds simple, but in reality, with the amount and complexity of information

required in manufacturing today, gathering and sharing requires sophisticated

technology.

Once you accept that quality cannot be “tested” into a product, but that it has to be built-in (and that to be compliant you have to demonstrate it), then your next question is not “Do we need technology to manage the process?” but “Which technology do we need to manage the process?”

Second, develop a process model that encompasses all common processes across the enterprise quality and compliance requirements. We have listed the processes used in a quality and compliance, as well as the normal activities, lists, and spreadsheets that are often used in a process. Table 1 provides a place to list your organization’s assets.

Understanding the components of process is half the battle.

Once you have the components - defining the linking and interconnections - the

“sharing” is the next (and often most complex) step. Rarely will one - or even

a small group of individuals - understand the majority of the relationships. It

is generally at this point that organizations turn to software providers that

have an intact, proven model. An example of one model is shown in Figure 5.

Understanding the components of process is half the battle.

Once you have the components - defining the linking and interconnections - the

“sharing” is the next (and often most complex) step. Rarely will one - or even

a small group of individuals - understand the majority of the relationships. It

is generally at this point that organizations turn to software providers that

have an intact, proven model. An example of one model is shown in Figure 5.

Connecting the dots and defining business requirements to reflect interconnections can take time. However, the result is a system that can:

To measure progress along the process, and provide insight into where along the process there are bottlenecks and larger improvements to be made, we can dive into the process and look at different levels of metrics. If we look at various phases, there are metrics that can indicate stage effectiveness (see Figure 6).

Tracking these metrics will provide insight as to what is

happening early on in the product lifecycle. Manufacturers know that pushing

engineering changes late in the product launch process increases costs and

increases the probability of mistakes.

Tracking these metrics will provide insight as to what is

happening early on in the product lifecycle. Manufacturers know that pushing

engineering changes late in the product launch process increases costs and

increases the probability of mistakes.

For most, this all seems like common sense. However, the Aberdeen report identified the following implementation challenges (see Table 2).

The conclusions:

“Quiz! from IQS streamlines our training information

management,” a Polyone representative said. “It reduces the time we spend

certifying procedure, safety or operational changes, as well as training

certification. Most importantly, it provides objective evidence that people

have met training objectives. The whole process of verifying the effectiveness

of the training system is now much simpler.”

“Quiz! from IQS streamlines our training information

management,” a Polyone representative said. “It reduces the time we spend

certifying procedure, safety or operational changes, as well as training

certification. Most importantly, it provides objective evidence that people

have met training objectives. The whole process of verifying the effectiveness

of the training system is now much simpler.”

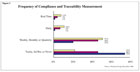

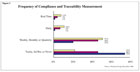

This example supports the Aberdeen report finding that best-in-class companies focus on solutions that operate in real time. The non-value-added time and labor required to support separate, stand-alone, non-integrated solutions will no longer be tolerated. Figure 7 explains measurement frequency and best-in-class status.

Another comment is that some management teams consider Microsoft Excel and e-mail to be software systems. They are not. They are personal productivity tools, which make them non-lean by nature and full of waste from non-value-added re-entry of information. The best-in-class companies have elevated compliance to the corporate boardroom and treat the software systems the same as ERP: business critical.

Also, be sure to avoid the quick fix. Consultants who sell technology services will present a solution that involves the creation of a data warehouse. The premise is that in order to get the metrics, we need to get data from all over the place and put it in a data warehouse. Sounds simple, makes sense. However, it avoids the operational excellence and common business challenge of improving the underlying business process. The time and effort spent on creating a data warehouse should be focused on creating the underlying common business processes. Creating the reports, dashboards and charts is easy. The processes your organization uses to collect the data for the charts needs to be the focus.

First, complete a physical inventory of all the software tools currently used across your quality, environmental health and safety, and financial (SOX) compliance efforts. This includes all spreadsheets, reports, databases, purchased software and homegrown legacy systems.

Second, develop a process model that encompasses all common processes across the enterprise quality and compliance requirements. A common model will have the elements shown in Table 3.

Compliance is a necessary evil in today’s marketplaces. Best-in-class organizations are turning compliance from a cost of doing business to a competitive advantage. Organizations who want to compete in a global environment need every competitive weapon at their disposal. Who’d have ever thought one would come disguised as compliance?

For more information on compliance systems, contact IQS Inc., 19706 Center Ridge Road, Cleveland, OH 44116-3637; phone (440) 333-1344 or (800) 635-5901; fax (440) 333-3752; or e-mail solutions@iqs.com.

A recent Aberdeen report on Compliance and Traceability provides insight into the development and maturation of manufacturers’ compliance programs. Best-in-class manufacturers understand that compliance programs are not just necessary activities, but a competitive advantage. The report relates that best-in-class companies are working toward common, single and enterprise compliance systems, and replacing outdated manual and one-off, non-integrated tools.

The report highlighted pitfalls that hamper most compliance initiatives: focusing on document rather than process management and a lack of metrics to measure success.

Why is it that focusing on process is such a challenge? To understand, we need to understand the history of compliance programs. In the 1980s and ‘90s, compliance programs were “checklist” audits. The effort to achieve compliance focused on having an answer for every item on the auditors' “checklists.” Companies focused on spreadsheets and manuals to meet early compliance requests. With the recent round of corporate corruption, front-page recalls and other high profile, compliance-related debacles, compliance has turned into a bottom line assurance that the process is operating in a safe and effective manner. Therefore, corporate and industry compliance programs are now focused on effective process. It is no longer acceptable to simply “have the answers” - inspectors want to know how you got the answers.

One additional challenge in the old way of doing things was the myriad governmental, industry and client standards that had to be met (e.g., ISO9000, AS9100, 21CFR11, TS16949, GMPs, ISO13485, etc.). It was not unusual for an organization to have 3-4 ongoing compliance initiatives, each with their own manual and checklists to pass each individual test. The good news about a process orientation is that once compliance is “built-in” to a process, the effort to demonstrate compliance requires minimal added labor, and audits go much smoother. A recent study by AMR Research concluded: “As business and IT recognize the overlapping requirements of individual compliance mandates, leaders are taking steps to build out a sustainable architecture that minimizes time and cost while maximizing future reuse.” (Source: AMR Research)

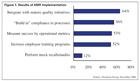

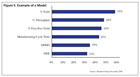

Figure 1. Results of AMR Implementation

A common framework for compliance initiatives is the backbone of process approach to built-in compliance. It allows for common information to be distributed and kept up to date. It provides distributed teams with the ability to work together off of one source of information. In complex manufacturing, this not only helps with compliance but provides companies that employ this strategy with a competitive advantage to reduce cycle time and reduce costs.

When AMR looked at how to develop this active compliance framework, they asked survey participants who had achieved best-in-class status how they had implemented the framework. The results are shown in Figure 1.

Not surprisingly, most organizations leveraged mature quality initiatives. There are two types of “quality.” First, there is quality control, which is a measurement function at the back end of the process. While an important part of manufacturing, this is not the type of quality that the survey is referring to. Quality management is the life cycle-long approach of building in quality functions to the manufacturing process that the survey refers to as “mature quality initiatives.”

Much like ERP streamlined the inventory and financial aspects of manufacturing, Enterprise Quality Management (EQM) is now providing that same streamlining function to the rest of manufacturing operations.

“The new role of the quality professional is to provide the organization with a seamless, integrated view of the business,” said John M. Cachat, chairman, IQS Inc. “The Quality Organization must provide the answers that cannot be found in financial and ERP systems.”

Figure 2. Manufacturing Product Life Cycle

Where Do You Start?

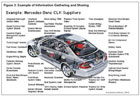

Not to sound mundane, but you start at the beginning. Quality is built-in from the planning and engineering stages. The knowledgeable source may add that the planning process has detailed product and process designs, failure analysis (FMEAs), etc. However, someone familiar with the entire manufacturing process will tell you that these important details and analyses that affect quality do not make it “over the wall” to manufacturing with any regularity.Organizations have tried vaulting documents and sharing them, but the result is that operations, inspection, purchasing and quality functions need data and information - not necessarily documents.

Figure 3. Example of Information Gathering and Sharing

When investigations begin on a quality failure, rarely is the answer that no one in the organization knew the problem existed, but that not all of the people in the organization that needed the information had it.

Figure 4. The Components of Process

Once you accept that quality cannot be “tested” into a product, but that it has to be built-in (and that to be compliant you have to demonstrate it), then your next question is not “Do we need technology to manage the process?” but “Which technology do we need to manage the process?”

Table 1. Developing a Process Model

Mapping and Modeling a Compliant Process

First, complete a physical inventory of all the software tools currently used across your quality, environmental health and safety, and financial (SOX) compliance efforts. This includes all spreadsheets, reports, databases, purchased software and homegrown legacy systems.Second, develop a process model that encompasses all common processes across the enterprise quality and compliance requirements. We have listed the processes used in a quality and compliance, as well as the normal activities, lists, and spreadsheets that are often used in a process. Table 1 provides a place to list your organization’s assets.

Figure 5. Example of a Model

Connecting the dots and defining business requirements to reflect interconnections can take time. However, the result is a system that can:

- Improve audit performance

- Dramatically reduce preparation time

- Reduce audit findings

- Reduce redundant labor

- Provide a competitive advantage

- Reduce product cycle times

- Reduce overall cost of producing product in-house and with suppliers

- Reduce warranty and recall impacts

- Improve quality (build products right the first time)

Figure 6. Example of Progress Measurement

Measuring Success, Beginning to End

Because building in compliance is a life cycle-long approach, some of the logical metrics to measure are the end result of the process: yield, throughput, etc. Those metrics will provide overall visibility to the process. In this case, unlike the process, the metrics start at the end.To measure progress along the process, and provide insight into where along the process there are bottlenecks and larger improvements to be made, we can dive into the process and look at different levels of metrics. If we look at various phases, there are metrics that can indicate stage effectiveness (see Figure 6).

Table 2. Implementation Challenges

For most, this all seems like common sense. However, the Aberdeen report identified the following implementation challenges (see Table 2).

The conclusions:

- Focusing on document rather than process management.

- A lack of metrics to measure success. The Aberdeen report further defines the actions taken by best-in-class manufacturers as the following.

- More than twice as likely as other manufacturers to have compliance and traceability centrally managed at the corporate level.

- More than twice as likely as other manufacturers to integrate disparate software solutions.

- 75% more likely to have process visibility and automated traceability than other manufacturers.

- More than five times as likely as other manufacturers to measure compliance and traceability performance in real or near-real time.

Figure 7.

This example supports the Aberdeen report finding that best-in-class companies focus on solutions that operate in real time. The non-value-added time and labor required to support separate, stand-alone, non-integrated solutions will no longer be tolerated. Figure 7 explains measurement frequency and best-in-class status.

Levels of Integration

It is important to define levels of integration. The three distinct levels are:- Integrating with enterprise quality and compliance management solutions.

- Integrating with other corporate systems (ERP, PLM, MES).

- Integrating the supply chain (customers and suppliers).

Another comment is that some management teams consider Microsoft Excel and e-mail to be software systems. They are not. They are personal productivity tools, which make them non-lean by nature and full of waste from non-value-added re-entry of information. The best-in-class companies have elevated compliance to the corporate boardroom and treat the software systems the same as ERP: business critical.

Also, be sure to avoid the quick fix. Consultants who sell technology services will present a solution that involves the creation of a data warehouse. The premise is that in order to get the metrics, we need to get data from all over the place and put it in a data warehouse. Sounds simple, makes sense. However, it avoids the operational excellence and common business challenge of improving the underlying business process. The time and effort spent on creating a data warehouse should be focused on creating the underlying common business processes. Creating the reports, dashboards and charts is easy. The processes your organization uses to collect the data for the charts needs to be the focus.

Table 3. Common Model Elements

Recommendations

This article discussed actions taken by best-in-class manufacturing companies. If you would like to develop a plan to improve your enterprise quality and management system, the steps are straightforward.First, complete a physical inventory of all the software tools currently used across your quality, environmental health and safety, and financial (SOX) compliance efforts. This includes all spreadsheets, reports, databases, purchased software and homegrown legacy systems.

Second, develop a process model that encompasses all common processes across the enterprise quality and compliance requirements. A common model will have the elements shown in Table 3.

Compliance is a necessary evil in today’s marketplaces. Best-in-class organizations are turning compliance from a cost of doing business to a competitive advantage. Organizations who want to compete in a global environment need every competitive weapon at their disposal. Who’d have ever thought one would come disguised as compliance?

For more information on compliance systems, contact IQS Inc., 19706 Center Ridge Road, Cleveland, OH 44116-3637; phone (440) 333-1344 or (800) 635-5901; fax (440) 333-3752; or e-mail solutions@iqs.com.

Links

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!