Creating Fire-Proof Seals for Aerospace and Defense: A New Approach to Preventing Cold-Side Ignition

This article provides an in-depth investigation into the interaction between material properties, sealant placement, and thermal performance.

In the aerospace and defense sectors, fire safety is not optional, it is mission critical. Engineers and materials scientists alike are well aware that even the most robust structural designs can be compromised by a small failure in thermal insulation or flame resistance. One of the most overlooked, yet vital, components in fire barrier performance is the sealant system itself, specifically, how it is applied.

Stabond Corp. has spent decades developing and supplying high-performance adhesives, sealants, and coatings for extreme environments. The company’s work spans across civil aviation, defense aircraft, and space systems, markets where safety margins are narrow and tolerance for error is virtually zero. All Stabond products are thoroughly tested per industry requirements. During a flame test of firewall sealants installed per SAE Aerospace Standard AIR4069, an unexpected failure mode occurred. Though the materials themselves passed individual certification tests, the assembly configuration described in the standard showed a troubling susceptibility to cold-side ignition after prolonged flame exposure.

This discovery prompted an in-depth investigation into the interaction between material properties, sealant placement, and thermal performance. The results point to a new best practice for sealing configuration, one that dramatically reduces the risk of backside ignition and strengthens fire containment in critical aerospace structures.

The Problem: Cold-Side Ignition in Standard Firewall Assemblies

Firewall sealants are engineered to block the spread of fire, smoke, and toxic gases in the event of combustion. In aerospace and defense applications, these materials are typically used to seal penetrations, fasteners, and joints in fire-rated walls or bulkheads, especially around fuel tanks or engine bays.

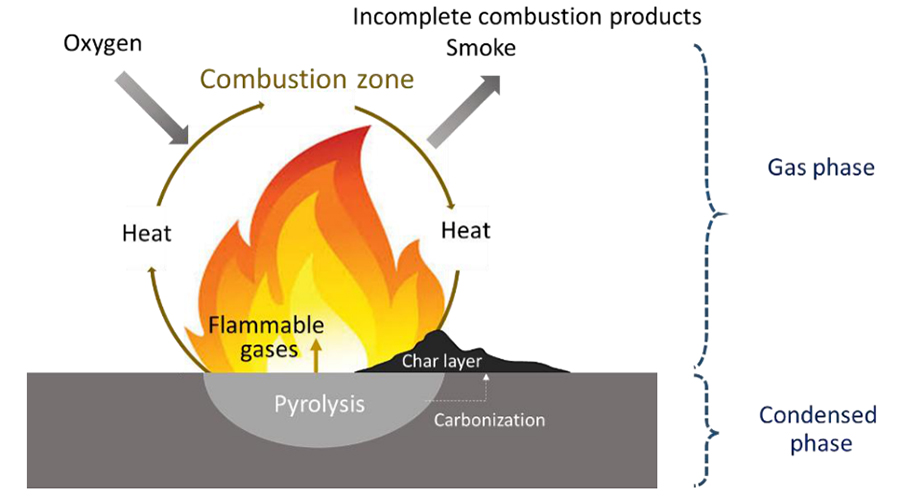

Aerospace-grade firewall sealants resist flame through a combination of three mechanisms:

- Intumescence – Upon exposure to high heat, many sealants expand into a carbonaceous char that insulates underlying surfaces and prevents combustion.

- Heat Resistance – Sealants resist thermal breakdown for extended periods, retaining mechanical strength.

- Adhesion – Sealants maintain strong bonds to metal and composite substrates, resisting delamination under stress.

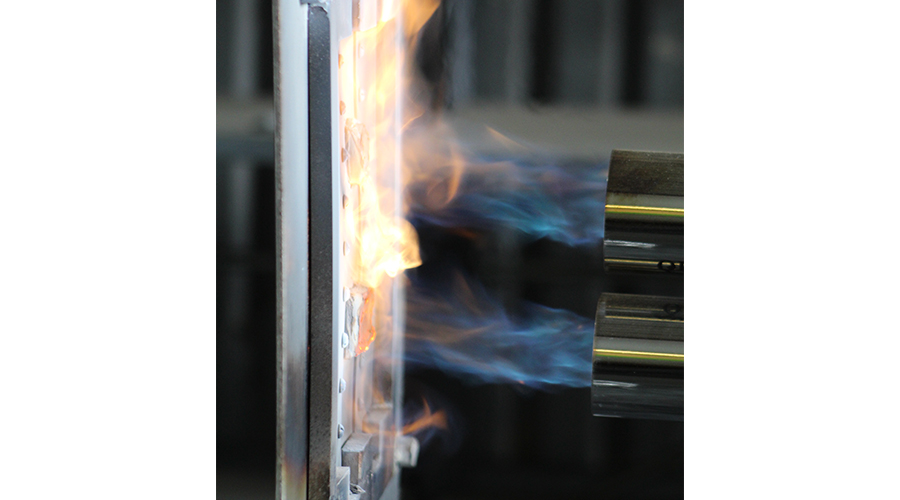

However, these benefits are dependent not only on the material itself but also on how it is applied. In real-world testing of sealants assembled in accordance with AIR4069, Stabond observed a consistent failure mode: backside or "cold-side" ignition occurring approximately 3.3 minutes into a standard flame test conducted at 2000 °F.

This scenario is especially dangerous because it can propagate flame through the sealed structure, counter to the purpose of the firewall system. Stabond's research indicates that the geometry and coverage of sealant in the AIR4069 assembly do not adequately protect the cold side from thermal degradation. Specifically, sealant on the cold side of the structure can volatilize and ignite if insufficiently insulated by material on the flame side.

Understanding the Standard: What AIR4069 Recommends

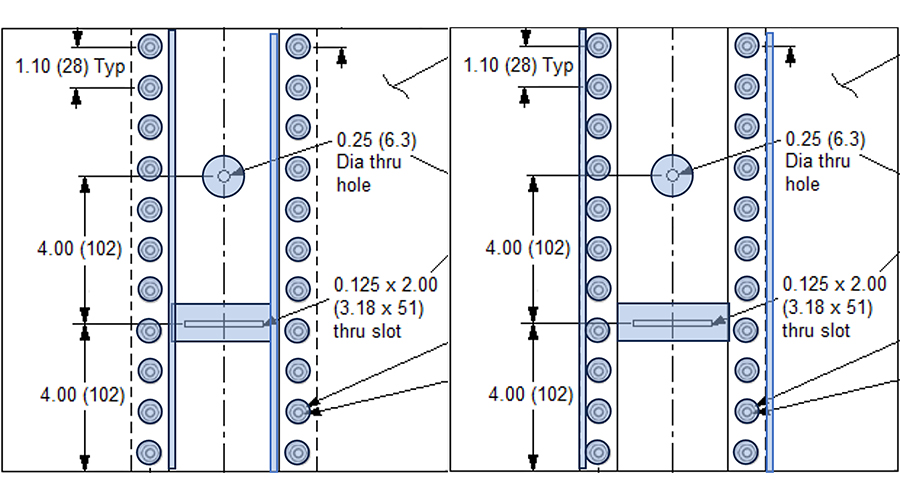

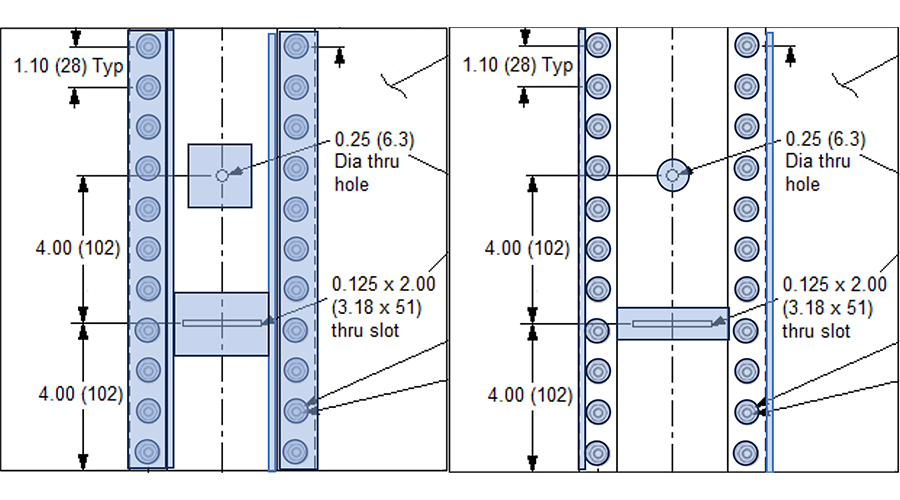

AIR4069 defines techniques for applying sealant to fasteners and joints in aircraft fuel tanks. It includes illustrations and instructions for installing fasteners and sealing holes and slots (e.g. Figure 3). These best practice techniques prevent leaks and ingress of chemicals that can corrode and degrade sealed structures. The AIR4069 guidelines specify the following:

Holes and Slots:

- Sealant must extend 0.5 inches from the edge on the flame side.

- Minimum thickness of 0.25 inches (flame side) and 0.18 inches (cold side).

Fasteners:

- Wet install with sealant

- On the flame side, overcoat fastener heads with sealant 0.10 to 0.12 in. thick, extending 0.25 in. from the edge

- On the cold side, fastener tails must be overcoated with sealant

- Substrate overlaps must be fillet sealed

In practice, this results in configurations where sealant may be exposed on the cold side to temperatures that can decompose the sealant, generating flammable material with high propensity to ignite.

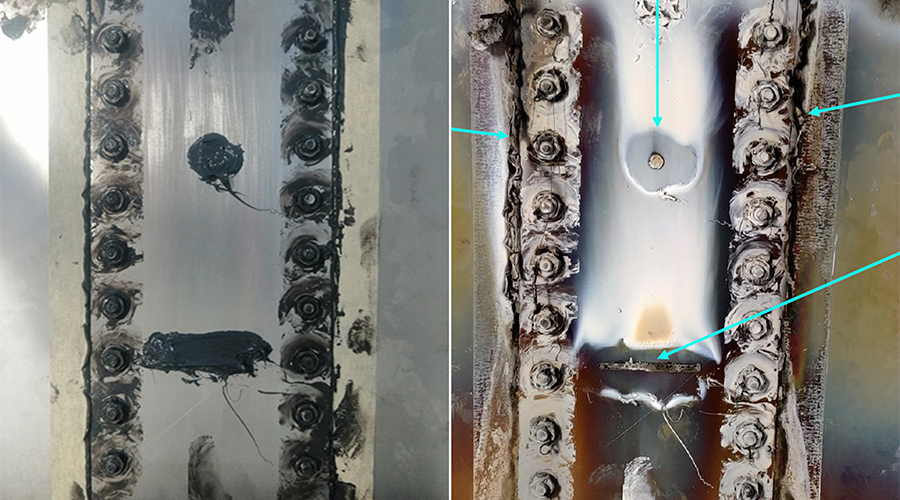

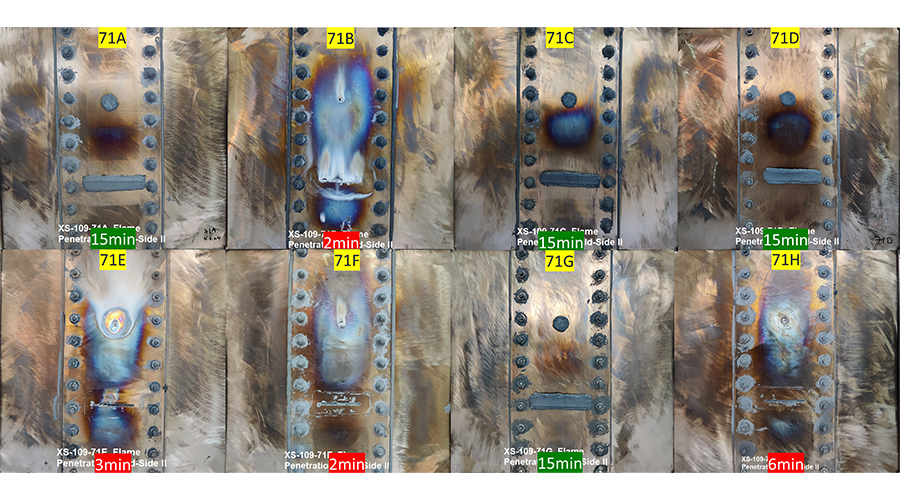

Figure 1 from Stabond's testing showed that, in multiple cases, sealant on the cold-side ignited during exposure to 2000 °F flame, demonstrating the need for improved thermal shielding in the seal design.

Hypothesis: A New Sealing Configuration

To address the issue, Stabond hypothesized that the sealant on the cold side must be protected by a more robust thermal barrier originating on the flame side. By optimizing sealant geometry, specifically increasing the coverage area and ensuring adequate thickness, the company could prevent pyrolysis and ignition, even under prolonged flame exposure.

Stabond’s proposed configuration includes the following revisions to AIR4069:

Flame-Side:

- Minimum 1-inch extension from hole or slot edges, with a consistent 0.125-inch minimum thickness

- 0.25 inch overlap to insulate overcoated fasteners and fillet-seals

Cold-Side:

Holes and slots should be sealed, with maximum 0.25-inch extension from edges and a minimum thickness of 0.125 inch

This design ensures that any sealant on the cold side is insulated by enough heat-resistant material in the event of a fire, preventing self-ignition and slowing the release of flammable gases.

Methodology: Putting It to the Test

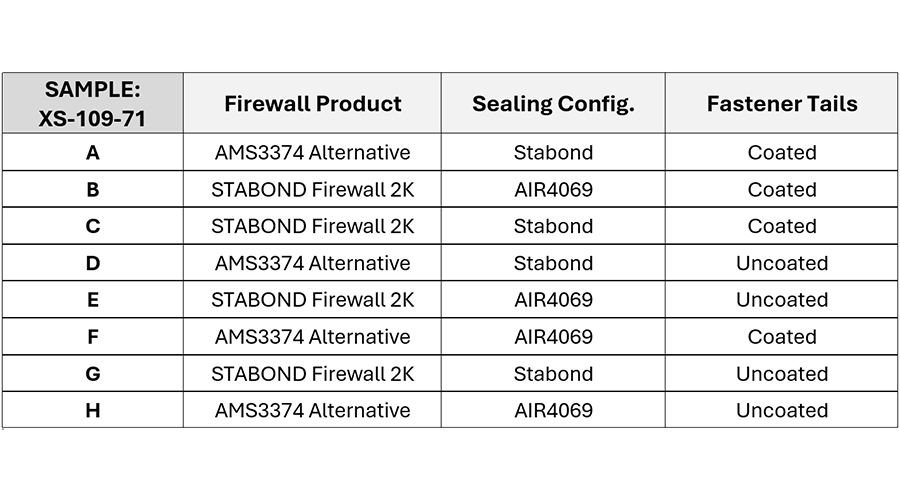

To validate this new sealing configuration, Stabond conducted a full factorial design of experiment (DOE), evaluating the effects of three variables:

- Product Type (AMS3374-qualified vs. STABOND Firewall 2K)

- Sealing Configuration (AIR4069 standard vs. Stabond recommended)

- Overcoating of Fastener Tails (Coated vs. Uncoated)

Each factor was tested at two levels, resulting in eight randomized test runs.

Materials Used:

- AMS3374-qualified firewall sealant

- STABOND Firewall 2K sealant

- AMS5517 stainless steel panels (0.06 inch thick)

- 10-24 zinc screws and hex nuts

- DS-108 solvent cleaner

Test Procedure:

Flame penetration testing was performed using a calibrated dual-torch system generating flame temperatures between 1850 °F and 2000 °F. Each test specimen was mounted without modification in a custom fixture and exposed to direct flame for up to 15 minutes. The primary measurement was the time to cold-side ignition.

Results: Configuration Makes the Difference

The performance of each configuration was quantified as the percentage of the 15-minute test time the specimen survived without cold-side ignition.

Test results showed:

- Specimens B, E, F, and H (AIR4069 configuration) failed before the 15-minute threshold. Self-igniting on cold side after a few minutes of exposure.

- Specimens A, C, D, and G (Stabond configuration) survived the full duration without backside ignition.

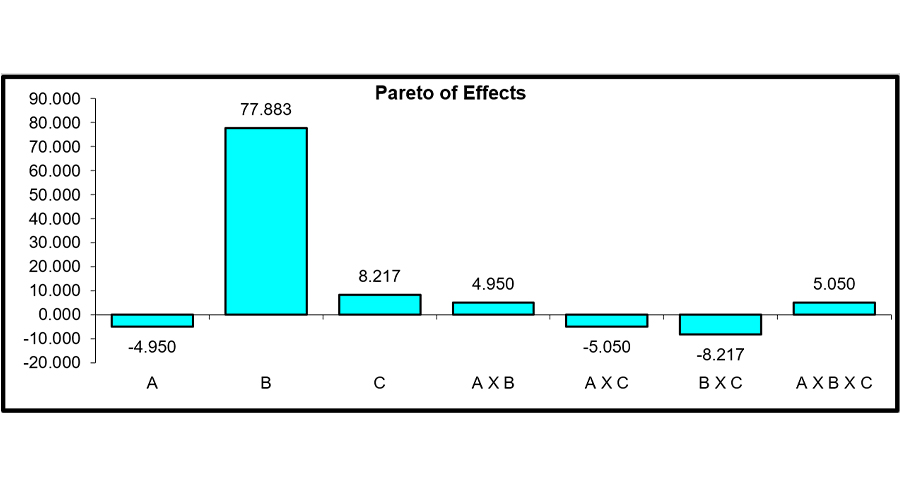

Statistical analysis, including ANOVA, confirmed that Sealing Configuration was the most significant factor influencing outcome. Product type and overcoating had small and insignificant measurable impacts. A Pareto chart (Figure 7) emphasized that the Stabond configuration resulted in an average 78% increase in success rate over the AIR4069 configuration.

Discussion: What This Means for the Industry

The implications of this research are far-reaching. While AIR4069 was developed as a standard for reliable sealing, its current guidance may inadvertently expose sealed assemblies to thermal failure under fire conditions.

Stabond’s testing demonstrates that even certified sealants can ignite if not properly shielded, and that shielding depends not just on material formulation, but on geometry and application technique. Protective sealant on the cold side, with no adjacent insulation, can become a liability rather than a safeguard.

The revised Stabond configuration not only improves safety but can also reduce rework and qualification failures during product certification. It is a simple, implementable change: extend coverage slightly on the flame side and ensure intentional, insulated coverage on the cold side.

Recommendation: A New Best Practice

To mitigate the risk of cold-side ignition in flame-exposed assemblies, Stabond recommend adopting the following sealing guidelines:

- Apply sealant at least 1 inch from the hole or slot edges on the flame side at 0.125-inch minimum thickness.

- Limit cold-side coverage to a maximum of 0.25 inch from the edge, with a matching 0.125-inch minimum thickness.

- Ensure any sealant on cold side is insulated with a 0.25 inch overlap of sealant on the flame side.

- Incorporating this revised sealing configuration can improve survivability during flame exposure and enhance compliance with critical aerospace and defense standards.

Conclusion

As the aerospace and defense industries continue to raise the bar on fire safety and reliability, it is imperative that sealing configurations evolve alongside material technologies. Stabond’s study shows that assembly geometry, specifically how and where sealant is applied, is a dominant factor in preventing flame propagation through firewall structures.

At Stabond, we are proud to contribute not just materials, but evidence-based design practices that improve the integrity and safety of high-performance systems. We encourage engineers, quality managers, and OEM partners to review their current sealing practices and consider adopting this enhanced configuration for better protection against the unthinkable.

In aerospace, there is no such thing as a small fire. Let’s seal it off before it starts.

Learn more about Stabond Corp. at www.stabond.com.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!