The RFID Revolution

Radio frequency identification (RFID) will make it to the item level - there's no question about it. The tidal wave of accelerating RFID R&D is progressively amassing the technical expertise of leading ink and adhesive manufacturers, surface treatment and printing equipment manufacturers, package printers, and electronics firms. Although the resulting investment to implement RFID solutions will be significant, the benefits of being an industry-leading supplier within the RFID chain can directly impact your bottom line. RFID adoption rates will surge during the next two years as consumer product companies (CPCs) comply with standards and mandates, reduce costs, and improve the tracking of goods from production through distribution.

The State of RFID Affairs

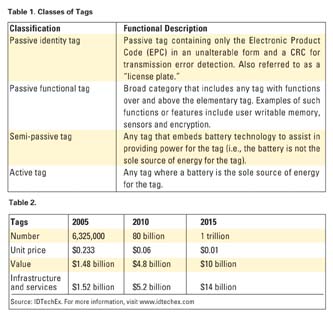

To define it, RFID is like a wireless barcode that identifies unique items using radio waves. A reader communicates with a tag, which holds a digital identification number (or serial number) in a microchip. An RFID system consists of the reader and transponders. Transponders (derived from the words "transmitter" and "responder") are attached to the items to be identified. They are often called "tags". The central ingredient in an RFID tag is an inlay. Inlays, also referred to as inlets and transponders, are typically composed of two pieces: a silicon chip and an antenna. An RFID tag carries product ID, product size, history, current status, instructions and location information. RFID uses radio waves at a specific frequency to identify individual items at a specific location.To assist business in understanding and using RFID, the EPCglobal has broadly defined a set of functional groups or "classes" of tags. Table 1 outlines those classes.

During the next decade, the number of RFID tags will grow exponentially as the cost of implementing RFID solutions comes down significantly (see Table 2).

Although the major drivers of the RFID movement (Wal-Mart, the U.S. Department of Defense and Proctor & Gamble) implied that they view RFID as part of the printing process, there's an inherent problem with this assumption. Current production on tag production lines is running at speeds of approximately 50 feet per minute. The system formats are also limited to widths of between 4-5 inches. These speeds and widths cannot be integrated with a conventional printing and converting line. In comparison, narrow-web flexo presses operate at speeds in excess of 500 feet per minute in web widths up to 14 inches wide. Solvent-based gravure presses run at speeds in the range of 3,000 feet per minute in web widths much greater, with the theoretical capability to produce over 50,000 antennae per minute.

Given this impediment to driving down the cost of RFID tag solutions, widespread implementation will be achieved primarily with new technologies in the realms of conductive inks, atmospheric plasma surface treatment, package printing/converting equipment and chip affixing devices.

Technological Bridge-Builders

Among the promising developments linked to the printing industry are conductive inks, which can be used in printing antennae on rotogravure presses. Companies leading the charge in this area include Precisia (div. of Flink Ink), Coates Group (div. of Sun Chemical), Dow Corning and Parelec. Highly conductive silver inks are highly filled with silver and proprietary additives to enhance conductivity of the transponding system. The cured inks exhibit high flexibility, which, combined with their excellent conductivity, creates a material ideally suited for portable wireless electronics such as RFID tags, smart cards, cell phones and PDAs. Using conductive inks to produce printed antennas at high speeds in place of copper, aluminum or screen-printed antennas is a significant milestone in RFID process development that, along with the affixing of the chip, relies on precise placement and adhesion to the tag inlay and subsequent adhesion of the inlay to facestocks.

Ensuring that solvent-based - and ultimately flexo-based - conductive silver inks adhere to base materials such as PET and PP suggests that surface treatment must be uniform and provide the necessary level of surface tension to create sufficient bonding sites across the web. Enercon Industries, a leading innovator in surface treatment technology, has had its Plasma3® atmospheric glow discharge web surface treatment system integrated into the manufacturing process of RFID tag producers to provide high-density plasma cleaning and functionalization of these surfaces. The Plasma3 allows for completely homogenous surface treatment without filamentary arcs (or "streamers") and offers the ability to apply variable chemistries to create covalent bonds with inks, coatings, and adhesives.

Emerging Developments

RFID innovators such as Precisia are rapidly moving toward developing high-speed production methods for complete assembly and attachment of RFID tags, a crucial step in keeping RFID tag production and attachment on pace with packaging throughput. Developments by Maxell, such as "Coil-on-Chip"® technology, feature the precise mounting of the antennae directly on the chip face to eliminate placement and connectivity deterioration issues relative to antennae leads. Knowing that RFID chips could be cheaper if alternative materials could be developed to those made from silicon, which cost around 20¢ each, 3M is currently evaluating pentacene as the chips' semiconducting material. Since pentacene can be spin-coated on thin, flexible substrates such as plastic film, it could turn out to be the route to very low-cost RFID technology. Existing prototypes of the chips are built on glass or plastic surfaces (the glass versions can communicate with a reading device several centimeters away). The 3M researchers are working on increasing that distance and getting the plastic version to communicate with the reader as well.One of the more interesting breakthrough applications of electronic devices with RFID technology includes adding a reader to a mobile phone, enabling easy two-way end-to-end information flow over cellular technology. This Nokia RFID solution uses passive, battery-free tags. The antenna enables the chip to transfer the identification information to a reader. The reader converts the radio waves returned from the RFID tag into a form that can then be passed on by way of cellular technology to PCs and to back-end systems under the 13.56 MHz frequency, globally the most widely used frequency. Touching the RFID tag with the phone allows for browsing of date-of-service information and reason-for-failure information, recording of meter readings and time/travel information, and the sending of automated messages.

The ability to manufacture RFID tags at commercial packaging speeds is several years away, but suppliers are working hard now to integrate their material and converting innovations with mandated retail and government guidelines in order to develop processes adaptable by packaging converters. RFID will make it to the item level - it's just a matter of time.

For more information on RFID, contact Rory Wolf at rwolf@enerconmail.com .

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!