Developing Pressure-Sensitive Adhesives for Low-Temperature Applications

When formulating pressure-sensitive adhesives for low-temperature applications, the advantages of SBS copolymers should be considered.

FINAT defines low-temperature adhesion as the ability of pressure-sensitive coated material to adhere at temperatures below 5°C. Today, many applications require adhesion that must be maintained at temperatures of -25°C or lower.

One of the main characteristics of pressure-sensitive adhesives (PSAs) is their viscoelastic character, which allows optimal mobility for wetting substrate surfaces in order to bond and obtain maximal adhesion, while absorbing energy as viscoelastic deformation to maintain an effective bonding. Viscoelastic character of an adhesive is given by the elastomeric polymer present in its formulation.

PSAs used in applications like tapes and labels for frozen food packaging and other applications in cold environments require special attention for the ingredients selection and, more specifically, in the polymer selection. At temperatures below the glass-transition temperature (Tg), a polymer has a brittle consistency and loses its deformation capacity. Consequently, an adhesive made with that polymer loses its mobility and elastomeric capacity to maintain the adhesion. It is therefore important to select a polymer that will adequately maintain its elastomeric characteristics at reduced temperatures; this is a low-Tg polymer.

Creating PSA Formulas

Derived from ancient formulations based on polyisoprene, PSA formulas have been traditionally based almost exclusively on styrene-isoprene-styrene (SIS) copolymers since their development on 1960s. Nowadays, PSAs are formulated with other polymeric bases, like styrene-butadiene-styrene (SBS), polyolefin (PO), etc. It is a specific challenge for formulators to obtain adhesives with lower Tgs for excellent performance at reduced temperatures, such as -25°C and sometimes lower. Table 1 shows Tg values for some polymers and other ingredients used to formulate PSAs.

As you can see, SBS copolymers have the lowest Tg of the group, including SIS copolymers. Other important ingredients in adhesive formulation that modify the Tg of the adhesive are the tackifiers. Usually, tackifiers used in PSAs have melt temperatures higher than the ambient temperature; however, some suppliers produce liquid tackifiers with a reduced melt point and reduced Tg.

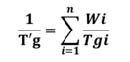

According to Fox’s definition of adhesive Tg, this parameter is directly influenced by the content of each one of the ingredients in the blend, including polymers, tackifiers and plasticizers:

where T’g = glass transition temperature (°K) for adhesive blend; Tgi = glass transition temperature (°K) for component i; and Wi = weight fraction of component i. This means that we need to carefully select each formula ingredient to obtain the adhesive performance in the temperature range required.

Dahlquist established criteria based on the Tg of the adhesive and its viscoelastic properties to define a performance window for PSA applications. As adhesive use has grown to include new applications, these criteria have been extended to cover them. Figure 1 graphs Dahlquist criteria and additional low-temperature applications. Clearly, it is essential to determine the Tg for the adhesive and its storage modulus at mentioned temperature to predict if the adhesive is going to perform according to the requirements for each application, including those at frozen temperatures.

Dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) is one of the analytical techniques used to determine both parameters in just one analysis for different materials, including adhesives. Figure 2 shows a typical graphic result for a DMA of a PSA. The analysis obtains both storage (G’) and loss (G’’) modulus in a wide range of temperatures; the ratio between both parameters is defined as tan d.

In Figure 2, cross points between G’ and G’’ define temperature zones where the polymer has different performance (those points can be identified by values of tan dδ=1). In the same way, the temperature at the peak of tan dδis identified as the Tg for the adhesive. Below this temperature, the adhesive becomes brittle and loses its capacity to transform energy in deformation; as a result, the bond can be broken easily. Above this temperature, the adhesive starts to perform as viscoelastic material, and this performance is maintained all over the temperature zone identified as rubbery plateau. Finally, in the last zone, the adhesive performs mainly as a viscous material and trends to flow.

Experimental Stage

Several low-temperature adhesives were formulated using SBS copolymers* to compare their viscoelastic performance with adhesives formulated using different base polymers. Samples were characterized by DMA. In addition, adhesives were evaluated for rolling ball tack at reduced temperatures using equipment specifically designed for this evaluation, in an attempt to find if the tack response at those temperatures can be correlated to the adhesive Tg.

Table 2 presents the main characteristics of two of the SBS copolymers used in this evaluation. An SIS copolymer was used as reference. Table 3 compares Solprene 4302 and an SIS reference copolymer using a standard PSA formula. The results show that both adhesives exhibited similar viscosity, but the SBS-based adhesive developed a lower softening point and reduced Tg. Similarly, SBS-based adhesive also developed a superior elastic modulus at 25°C and maintained a higher tack at lower temperatures (rolling ball tack). According to these results, manufacturers could use a formula based on Solprene 4302 instead of SIS copolymers to improve low-temperature performance for PSAs.

Figure 3 presents the comparative results of DMA for both adhesive formulas, where the previously mentioned differences in performance can be observed. In Table 4, a similar comparative for Solprene 9618 was created using the same SIS reference copolymer. It can be observed that the adhesive formula based on Solprene 9618 developed almost 30% lower viscosity and similar softening point than the adhesive based on the SIS copolymer. In addition, Solprene 9618 developed superior elastic modulus and an almost 16°C lower Tg than the SIS-based formula. Finally, for the Solprene 9618-based formula, an excellent tack was maintained at lower temperatures (such as -5°C) when the SIS-based reference formulation experienced loose tack at 0°C. The comparative results of DMA for both adhesive formulas are presented in Figure 4.

Conclusions

When used to formulate PSAs to perform at lower temperatures, SBS copolymers offer the following advantages over SIS copolymers:

• Develop lower Tg adhesives to maintain excellent performance at cold temperatures

• Develop a more extended performance plateau than SIS-based formulations for extended temperature range resistance

• Develop superior elastic modulus to maintain improved adhesion

• Maintain tack at lower temperatures for application in colder ambient

• New multiarm SBS copolymers developed up to 30% lower adhesive viscosity, for energy savings by low-temperature adhesive application

For additional information, call (281) 874-0888, email nneonis@dynasol.com.mx or visit www.dynasolelastomers.com.

Author’s note: Special thanks to the Dynasol adhesives laboratory technical team, including Martha Dzul A., Laura P. Alonso and José Luis García V.

References

1. Satas, Donatas, Handbook of Pressure Sensitive Adhesive Technology, ed., Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1989.

2. Esquivel De La Garza Alejandro C., “Optimize Your Adhesive Formulation & Achieve Superior Performance at Low Temperatures with Dynasol SBS/SBR Polymers,” webinar, SpecialChem, 2013.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!